Wet Bulb Temperature Explained

As the Earth Heats, Understanding Wet Bulb Temperature Becomes Critical

Note: since publishing on the 11th, a kind Alaskan climate scientist provided information clarifying ongoing confusion between the commonly used term Wet Bulb Temperature and Wet Bulb Global Temperature. This is reflected in new information below under Wet Bulb Temperature vs. Wet Bulb Global Temperature.

Please see my new article Stunning Wet Bulb Temperature Update, as well. A Pennsylvania State University study has shown WBT is much lower than the previously assumed. It’s important to be aware of these findings. I found this essential information one day after publishing this article.

A couple of years ago, I had never heard the term wet bulb temperature. Now, however, with rising global temperatures, it’s a term which we should all understand.

With the return of El Niño, scientists think 2023 could become the hottest year on record. Tuesday, July 4th was briefly the hottest day humans ever recorded on Earth. The average global temperature hit 62.92° F (17.18° C). That record was tied the next day, Wednesday, and surpassed Thursday, as global temperatures climbed to 63.01° F (17.23° C). These were the three hottest days on the planet humans have ever lived through.

In India, 96 people died from heat exposure as of June 19 when temperatures reached as high as 115° F (46° C). In April, India experienced a heatwave which saw temperatures in New Delhi exceed 104° F (40° C) for seven consecutive days. In Ballia District, where three million reside, the daily high temperature over the same period hovered around 109° F (43° C).

Temperature records are tumbling across Asia, from Singapore to Vietnam. Dozens of heat records have fallen in Siberia as well, where temperatures exceeded 100° F (37.7° C) in early June. Heat in Siberia breaks records every year now. Siberia, like Canada, is home to boreal forests that store vast amounts of ancient carbon in the permafrost. As the permafrost thaws, methane bubbling to the surface in newly formed lakes is being released. How long before millions of years of sequestered carbon starts to be released, too?

Trees of course store carbon, and boreal forests are one of the critical systems that regulate climate on the planet. In fact, they are a tipping point. So far, 22.2 million acres of boreal forested area have burned in Canada this year, nearly three times the amount when I wrote this article just weeks ago, shattering a 34-year record with three months of fire season to go.

In other words, the world is just going to get hotter.

As of June 29 at least 100 people have died in Mexico from heat, where temperatures climbed close to 122° F (50° C) in areas according to the health ministry. In Texas, at least 13 have died from heat as of June 28. Bear in mind though that body counts from heat deaths are likely undercounted from misclassification, for instance heart attacks caused by heat stress, and delays in coroner reports. This in a state where governor and social terrorist Greg Abbott recently signed a bill denying workers water breaks.

If these figures don’t sound impressive, consider the 200-year-old scientific and medical journal the Lancet, which pegged direct deaths from heat at 356,000 in 2019. Those figures don’t include deaths from associated events such as increased hurricanes, fires, flooding, and mudslides.

The warmer temperatures of El Niño haven’t peaked yet and are expected to last for years, making this is an important time to know about wet bulb temperature. Many of us have heard this term, but may not fully understand it, or how it applies to each of us individually based on a range of factors.

What is Wet Bulb Temperature vs. Wet Bulb Global Temperature

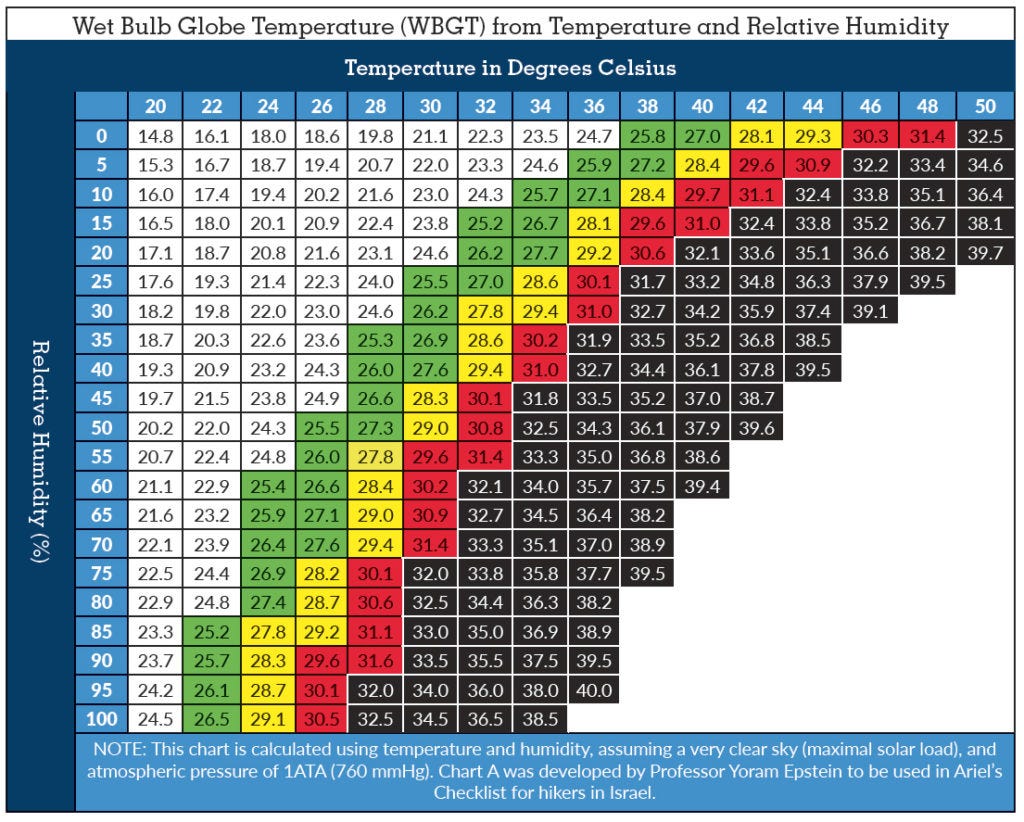

Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT) was a measurement developed by the US military in the 1950s to identify levels of heat stress in soldiers. WGBT accounts for not just temperature, but, humidity, wind speed, and sunlight exposure. It’s similar to the heat index, with which we are all familiar. It’s a useful measure outdoors.

Wet Bulb Temperature (WBT) combines just two parameters, dry air temperature (as you’d see on a thermometer) with humidity.

If you were to slide a wet cloth over the bulb of a thermometer and pull it away, evaporating water from the cloth will cool the thermometer down. This lower temperature is the WBT, which cannot go above the dry temperature. If humidity in the surrounding air is high, however, less evaporation will occur, so the WBT will be closer to the surrounding air temperature. WBT is a more useful measure for indoor conditions where wind and sun are not factors.

The chart below, although called Wet Bulb Global Temperature, only combines the two parameters of temperature and humidity.

A WBT of around 95° F (35° C), is about the limit of human tolerance. Above that, our bodies can’t lose heat efficiently enough to maintain a healthy core temperature.

Conditions that lead to a wet-bulb temperature of 95° F vary. With no breeze, sunny skies, and 50% humidity a deadly wet-bulb temperature is around 109° F, (43° C) while in dry air, temperatures up to 130° F (54° C) could be survivable.

How Excessive Heat Affects our Bodies, Brains and Organs

Our normal body temperature holds steady around 98.6° F (37° C) and works constantly to balance heat loss and gain. We have a narrow temperature range in which we can function. We’ve all experienced high temperatures from being sick with a virus and know how that feels. When our core temperature gets too hot, organs can shut down. We know that, too. Extreme heat can cause severe kidney and heart problems, and even brain damage.

Many of us have experienced environmental heat over 100° degrees as well. It’s debilitating. We look for shade. We stay indoors in air conditioning or at least in front of a fan. If our body temperatures get to about 104° F (40° C), organs begin to fail, and unless we get into cooler conditions immediately, we die.

Generally, our skin temperature needs to be below 35° C, meaning WBT must be below 35° C.

We depend on sweating to compensate if our core heats up. If humidity is high—the air loaded with water vapor—our ability to cool ourselves is rendered ineffective. Sweat can’t evaporate quickly enough to compensate.

Another factor is the length of heatwaves. If high temperature conditions don’t cool sufficiently at night (like in The Midnight Sun), we are more endangered, particularly children and elderly who require extra time to recover for the next day. Underlying health conditions are a factor, too, as is where you live in the world. People who live in more moderate climates, are likely more susceptible to heat related deaths than those who live in hotter ones.

This means heat tolerance varies from person to person. Your WBT and mine are highly personal.

Safety During Extreme Heat, a Lethal Example of Inequality

The world is an incredibly unfair and unequal place. 40 percent of the world’s population live in hot tropical regions, where they are currently exposed to at least 20 days a year of life-threatening temperatures. That figure will increase. Most of those nearly 3 billion people living in the hottest parts of the world, don’t have air conditioners. Only 16 percent of people in Brazil and Mexico own them, 9 percent in Indonesia, 6 percent in South Africa, and 5 percent in India. The World Health Organization estimates that, by 2050, more than 255,000 people could be killed annually from extreme heat waves, on page 21 of this document.

Of course, running air conditioners increases global warming. Quite the conflict, don’t you think?

If had my way, I would pack the air-conditioned mansions of the billionaires who have created the #ClimateEmergency with Global South people, and send these sociopaths on tropical vacations (sans yachts, private jets, luxury hotels, and personal neck air conditioners, thank you) to see if that changes their perspective. Bon voyage, happy Dengue fever, everyone.

Staying Safe During Extreme Heat, for Those of Us Who Can

Assuming you’re safe if you live in the Global North is no longer safe to assume. Cities are hotter than the countryside, and poor people who live in cities heated by concrete, and suffering from a lack of access to shade and air conditioning are extremely vulnerable.

Cities need to have cooling centers. They need to plant trees and create shaded parks.

Temperatures over 100° F are no longer unusual in places that never saw those extremes before. That makes them vulnerable. Look at Canada and the Pacific northwest. Like Mexico, Brazil, Indonesia, South Africa and India, those places don’t have much air-conditioning. They never needed it, and some places that saw extreme heat when I was a kid can only be worse now. I well-remember sweating my ass off in my grandparent’s house in Indiana in the 1970s and the heat of Cincinnati, Ohio, where air conditioning was mandatory. Opening your front door was like a blast of death on some days. We’re not familiar with or physically acclimated to this kind of increasing heat.

The first rule, of course, is to drink plenty of water. Many of us routinely forget to do that.

We have a thermostat at the base of our brain in the hypothalamus, that reads signals from our skin, muscles, and organs. If we’re too hot, we’re told to sweat. If we’re dehydrated, we can’t sweat. So drinking water up to two liters of an hour or a bit over a half a gallon is essential. Lack of water can result in overheating organs. Water, is also critical to take up electrolytes and salts, which maintain blood acidity, which allows our cells to function.

Signals of dehydration can be weaker in older people, so be aware. If your urine is brown, you’re going down. So drink. Keep an eye on the elderly, young children and babies.

Pay attention to alerts from your local health and weather authorities.

If you have air conditioning in your home, make sure it’s serviced. Ditto for your car. Keep at least a few gallons of water in your vehicle and buy a AAA plan. It’s inexpensive. A guy in Texas just died in his car. His air conditioning wasn’t working.

Pull curtains and blinds appropriately to bounce heat out. Shut windows when it’s hotter outside than inside, open them when it’s the opposite. Using blinds and curtains wisely helps with strain on the grid if you’re running air-conditioning as well. Black-outs at 110° aren’t cool. They could kill somebody.

Know your neighbors, especially if you live alone. You may need them, or they you. If you’ve got a basement, consider setting up a cool safety spot down there.

Keep ice packs handy. An ice pack on the back of the neck can do wonders. As a cyclist, I well-know.

Don’t sunbathe when it’s hot, even if you’re hot. Dead isn’t sexy. Also, that poor guy in Texas should have known better. The high was 126° F. The low was 99° F.

As always, thank you for reading and stay safe.